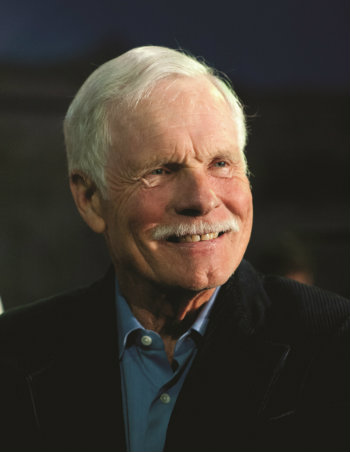

Land Report 2017 Legacy Landowner: Ted Turner

Land Report 2017 Legacy Landowner: Ted Turner

Turner01_fi

Like the North Star above his beloved Flying D Ranch, our 2017 Legacy Landowner has been a constant beacon, ceaseless in his support of all God’s creatures and His lands.

When was the first time you became aware of Ted Turner the Landowner?

Not Ted Turner the Sportsman, who successfully defended America’s Cup in 1977 and whose Atlanta Braves won the 1995 World Series. And I’m not referring to your first recollection of Ted Turner the Cable Guy, who developed the pioneering superstation WTBS in the late 1970s and launched CNN in 1980. I’m talking about the lifelong hunter, the devout fly-fisherman, the champion of the American bison, a landowner who stewards some two million acres in the US and Argentina.

Vermejo sits at a special corner of the Old West, where the Great Plains meets the Southern Rockies. That country has always called out to me, which is probably why the news caught my eye. Come to find out, that little blip in The Times triggered memories of a summer spent at the Philmont Scout Ranch next door to Vermejo. Thanks to two decades’ hindsight, I can credit that one transaction with generating the spark for this magazine.

Which was precisely a part of Turner’s plan. Our 2017 Legacy Landowner has assembled an amazing collection of properties. But that’s only half the story. He is equally adamant about inspiring you and me and anyone else with an interest in land to better this world of ours.

Think about it. Then prove him right.

Turner’s commitment to conservation is no recent occurrence. It’s a lifetime phenomenon that dates back to his earliest years, one that has remained a continual touchstone.

“There are two Teds,” says friend Tom Brokaw. “There’s this kind of bombastic Ted, and then there’s this very keen ornithologist, a guy who cares about the land. It’s not just a trophy to Ted. He cares about land organically. He knows the birds on the wing. He knows the flowers. He knows the grass. When he turned 75, somebody sent me a description of what he was like when he was a kid. He was a great birder. He was a taxidermist. So when I hunt with him, he’s very attentive to the process. He wants to make sure he gets it right.”

Mike Phillips has served as director of the Turner Endangered Species Fund since its founding in 1997. Over the last two decades, the Montana state senator has witnessed this mind-set firsthand.

“Ted seems to have a chronic ability to focus on foundational aspects of import,” Phillips says. “You’re talking about a guy who has assembled a body of work that is strangely robust. He has this knack to drive to the most important common denominator. Ted put an easement on St. Phillips Island [his 4,680-acre South Carolina property] in the early 1980s. Nobody was talking about conservation easements back then. But he saw a need for acknowledging the power of incentives to protect land.”

Turner’s rehabilitation of Montana’s Flying D Ranch was anything but low profile. He paid less than $200 per acre for the 113,613-acre ranch. In addition to recognizing the Flying D’s value as a long-term investment, he was floored by its scenic splendor and the abundant wildlife. Its traditional use as a cattle ranch? Not nearly as appealing.

Russ Miller was in charge of Hall and Hall’s ranch management division when Turner bought the Flying D. He was subsequently brought on board as the first general manager of Turner’s western ranches.

“When Ted bought the Flying D from Bobby Shelton in 1989, I was still at Hall and Hall. He invited me and ranch manager Bud Griffith to the Spanish Creek house. Ted was on the porch with a book of Karl Bodmer prints in his lap. We all looked down at the Bodmer prints, and then we looked out across the landscape and saw a bunch of tractors putting hay up. There were power lines and fences and Angus cattle. And Ted looked down at the book again and up at the landscape, and down at the book and up at the landscape. Bud and I were following his head — kind of like watching a tennis match.

When Turner learned that South Dakota’s Standing Butte Ranch was going to auction and about to be divided up, he preserved the pristine prairie by buying it outright.

“Then Ted said to Bud and me, ‘You see this watercolor?’ It was a painting of bison crashing through the underbrush in Northern Montana. He said, ‘That’s what I want the Flying D to look like. Those Angus cattle? Gone. Those tractors putting up hay? Gone. Those power lines? Gone. That’s your job, boys. And what do you know about bison?’

“‘Not much’ was the answer.

“‘Well, you better start learning because that’s what we’re going to be running.’”

Turner Enterprises President and CEO Taylor Glover enjoys the closest of relationships with Ted. The two have been friends and colleagues for decades. He still gets a chuckle out of the experience: “I’ll never forget when Ted acquired the Flying D. I think that big valley is seven miles long and four miles across. He said, ‘I can’t wait to get those fences out of here. All I want to see is bison.’ By golly, if you go there today, that’s exactly what you see.”

There are those who have taken umbrage with Turner’s methods, in particular, cattlemen who resented the hasty exit of their preferred ungulate from ranches bought by Turner.

But others, especially those who know Turner personally, share a different story. Take for instance John Malone. I tracked down America’s largest landowner in his Denver office. His esteem and affection for his longtime cable industry colleague and close friend dominated our conversation.

“You just love the guy,” Malone began. “Every engine needs a spark plug. That’s Ted. He has so many youthful enthusiasms in so many ways. I’m the anchor that weighed him down, the albatross around his neck. But Ted has this incredible enthusiasm. It literally carried him over obstacles facing our industry. And he was always 100 percent all in for our industry.

Like Turner, Malone has acquired iconic cattle ranches out west. In New Mexico, the historic TO Ranch sits in the shadow of Vermejo Park. And Malone’s 290,100-acre Bell Ranch, which was originally a part of the Pablo Montoya Land Grant, is every bit as steeped in territorial history as Vermejo.

“Ted has this romance with the West. He loves everything Native American and wants to take his ranches back to the pre-Columbian era,” Malone says.

Marketing his own bison proved to be precisely the sort of situation where Turner’s “spark plug” attitude was required. Malone singles out Turner’s innovation, creativity, and skillfulness as keys to the rise of the bison industry. Not that it was always easy.

“I remember back in the early days. Ted was just getting into bison. Some years he’s brag about how high the price of bison was. Other years he’d call me and ask, “Do you know what a heifer calf just brought in Fargo? Forty dollars!” Malone says with a laugh.

At 30 Rock, another friend shared a far different perspective on the same story.

“Meredith and I when pheasant hunting in South Dakota with Ted. She’s very fond of him, and he of her. At one point, the birds were down, and I said ‘Ted, what I really want is for Meredith to get an appreciation of what you’ve accomplished. We’re going to go up on one of the higher hills, because when you’re up there and all the fencing is down and the bison are on the grass, it’s 1895.’ It really is,” says Brokaw.

This duality — creating a profitable financial model on his lands while preserving and enhancing their many varied habitats — plumbs the essence of our 2017 Legacy Landowner.

“It is taut and tight, and it is all Ted Turner,” says Mark Kossler, the general manager of Turner Ranches. “In some circles, Ted is known as a hardball businessman. He knows how to make money. He knows how to run profitable businesses, and he can be tough to deal with in a business environment. Fair, but tough. On the other hand, he is known as a conservationist who takes conservation very seriously, and he wants to manage his properties and have other properties he manages conserve species. So that mission statement is all Ted Turner.”

Bison cows and calves graze on Turner’s Standing Butte Ranch, one of nine properties he owns on the Great Plains.

This challenging mission statement highlights Turner’s unique capacity — to use Mike Phillips’s insight — to drive to the most important common denominator.

“When I managed Vermejo Park and the Flying D for Ted, I always had the view that first and foremost, Turner Ranches was in the grass business. It’s been three years since I took over for Russ Miller and now oversee all the ranches. And I’ve been overlaying that philosophy on all of our ranches. Everybody wants to talk bison. Bison are sexy. They’re in vogue. But bison are really a means to take our grass crop and market it or monetize it. Let’s broaden that out a little bit. It’s not grass we’re monetizing. It’s habitat. How we manage these properties makes the habitat on them, the forage, and the soils underneath the forage either more vibrant, more resilient, and more diverse, or less. That is the basis of our management of Turner Ranches. We do spend a lot of time talking about bison and bison production, but at the core of what we do, it’s really all about the habitat,” Kossler says.

Yet it’s only when Kossler shares a second anecdote that the Turner Ranches’ mission statement and its balance of commerce and conservation comes into focus.

“A year ago, we had a catastrophic fire on the Z Bar Ranch in Kansas. It encompassed 450,000 acres and burned off 96 percent of the Z Bar. Our bison herd there is 800 cows and a complement of yearlings and breeding bulls. But we lost just six animals. Why so few? Because of our prairie dogs. By nature, prairie dogs overgraze. That’s why so many ranchers consider them pests. They kill off perennial vegetation and leave bare ground and burrows. Which is why the bison went to the prairie dog town. They hunkered down where there was no grass to burn, and the fire blew right around them. It was hot and fast moving, and the losses could have been sky-high. But we manage for habitat, and on the Z Bar, that includes non-commodity species like prairie dogs,” he says.

Ultimately, The Land Report did not select Ted Turner as its 2017 Legacy Landowner for a single accomplishment, such as assembling the most diverse portfolio of private land nationwide or championing the bison and building the world’s largest private herd. For that matter, it wasn’t for a series of accomplishments. It was because of his attitude — “his incredible enthusiasm,” to reiterate the phrase John Malone used.

That enthusiasm has enabled him to impact millions on earth who don’t know his household name, don’t recognize his famous face, and aren’t familiar with a single one of his accomplishments.

“Ted has done more for humanity with a focus on the environment than anybody who has ever lived,” says Mike Phillips.

“Now, let’s think about this for a moment. You can forget everybody that lived before 1850. Forget them all. No one who lived before 1850 counts because they weren’t too terribly concerned about the humanization of the planet, the degradation of the planet through human activities. So we’re only talking about contemporary folks. Then you think about Theodore Roosevelt or Jimmy Carter. They both did tremendous things, but they did so as public servants. You think about groups like The Nature Conservancy. They do beautiful work, but they’re a member-based organization. So show me, find me, tell me one private individual who has done more for humanity with a focus on the environment besides Ted Turner,” Phillips asks.

And where does the impetus come from to make such an earth-changing impact on your fellow man? Taylor Glover volunteers the answer.

“Bringing ecosystems back into balance by reintroducing native species like bison and rainbow trout is a virtuous cycle that excites Ted,” he says